1889 Daimler Wire Wheel Car

|

Price |

-- |

Production |

-- | ||

|

Engine |

565 cc v2 |

Weight |

-- | ||

|

Aspiration |

natural |

Torque |

-- | ||

|

HP |

1.5 hp @ 700 rpm |

HP/Weight |

-- | ||

|

HP/Liter |

2.7 hp per liter |

1/4 mile |

-- | ||

|

0-62 mph |

-- |

Top Speed |

-- |

(from Daimler Press Release) Paris World Exposition, 1889: Presentation of the Daimler wire-wheel car

-- The twin-cylinder

V-engine proves a pioneering development

-- The four-speed manual transmission becomes a model for later

motor vehicle transmissions

-- Daimler designs are the catalyst for the French car industry

In 1889 the eyes of the world turned to Paris and the World Exposition. The biggest attraction – in all senses of the word – was the tower wrought in iron by Gustave Eiffel. But something else that fascinated the crowds of visitors to the show was the use of electric bulbs to illuminate many of the exhibition stands – the very epitome of the modern age. Never one to be left behind, Gottlieb Daimler installed thirty electric light bulbs around his stand, powered by current generated from his “illumination car”, a mobile mini power station equipped with Daimler engine and electricity generator. The light from his bulbs highlighted one exhibit in particular that had yet to achieve its breakthrough – the four-wheeled “wire-wheel car”.

Although it received

considerable favourable interest, the car failed to strike many

visitors as sensational. And yet only three years earlier, Gottlieb

Daimler, aided and abetted by the engineer Wilhelm Maybach, had

built the world’s first four-wheeled automobile – a carriage

equipped with internal combustion engine and steering device. 1886

was also the year in which Carl Benz presented his Patent Motor Car;

this, too, was on display at the World Exposition. But the new

Daimler automobile featured a number of ground-breaking innovations:

the wire-wheel car had a two-cylinder

petrol-powered V-engine and a geared manual transmission. The same

engine also powered two boats brought by Daimler to Paris and with

which he proved the innovative drive system’s viability for

watercraft on the River Seine. In short, then, Daimler’s was an

impressive display of products.

The first automobiles in 1886 had succeeded in demonstrating what was feasible in principle. But they had also shown their limitations. The output of 1.1 hp (0.8 kW) at 650/min achieved by the Daimler single-cylinder engine was inadequate for many applications. Maybach multiplied the power by adding a second cylinder canted at 17 degrees – thereby giving rise to the world’s first V-engine. In common with the earlier single-cylinder engine, nicknamed the “grandfather clock” on account of its vertical shape, the V-engine featured water-cooled cylinder heads and was equipped with the curved-groove valve control initially favoured by Daimler. The displacement of 565 cubic centimetres was sufficient to develop an output initially of 1.5 hp (1.1 kW) at 700/min. A major advantage of the new engine was its lightweight design – it weighed just 40 kilograms per horsepower, half as much as its predecessor. The patent awarded to this engine in 1888 (DRP No. 50839) already included designs with cylinders in parallel and in boxer configurations, overhead exhaust valves and cam-operated rather than curved-groove valve control.

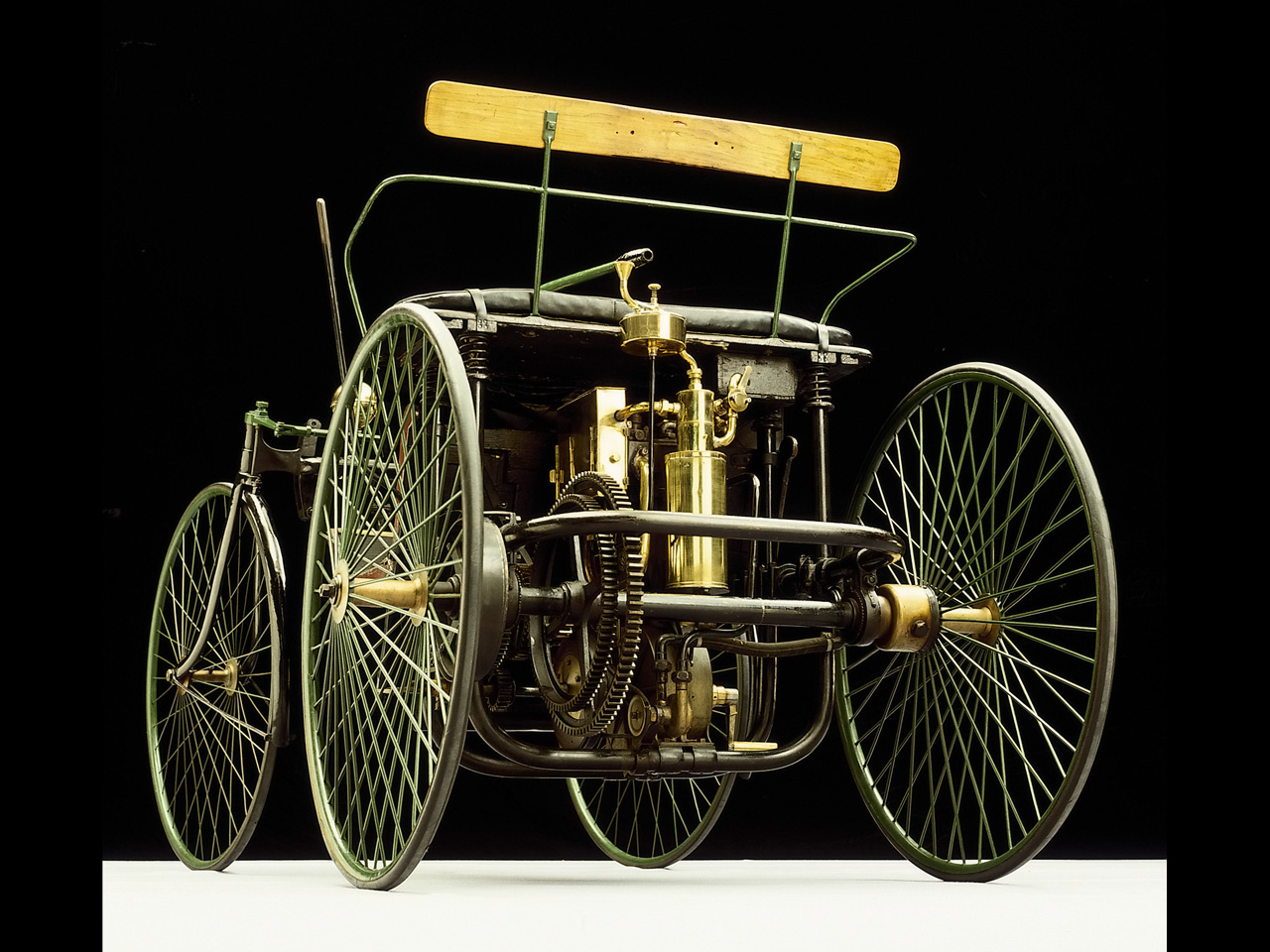

The twin-cylinder V-engine was the perfect drive system for the highly-elegant wire-wheel car initiated by Maybach, so called for its slender iron wheels. This was an entirely new design. Of particular note are the technical similarities with the bicycle, in particular the frame and chassis, which is why in his design sketches Maybach also referred to the vehicle as a “quadricycle”. The frame and wheels of the wire-wheel car were supplied by Strickmaschinen-Fabrik AG of Neckarsulm, a well-known local firm of bicycle manufacturers, which later achieved international fame under the name NSU.

Maybach additionally used the robust tubular steel frame of the lightweight vehicle as a conduit for coolant water and positioned the engine in the rear. On the rear axle beside the right-hand wheel he fitted a sealed bevel gear differential, and on the left wheel a brake drum with a band brake operated by a hand lever from the driver’s seat.

There were initially problems with the steering – axle pivot steering did not appear on a four-wheeled vehicle until Benz introduced it in 1893 – which explains why the design documentation still contained a draft for a “three-wheeled velocipede” with steerable rear wheel. This three-wheeler design soon disappeared back into the drawer, however, when a different solution was found to the steering problem with the four-wheeled wire-wheel car. Here, using the same principle as a bicycle, each of the front wheels was individually mounted in a fork and linked by a track rod. So when the steering lever was turned, the wheels tracked a common radius.

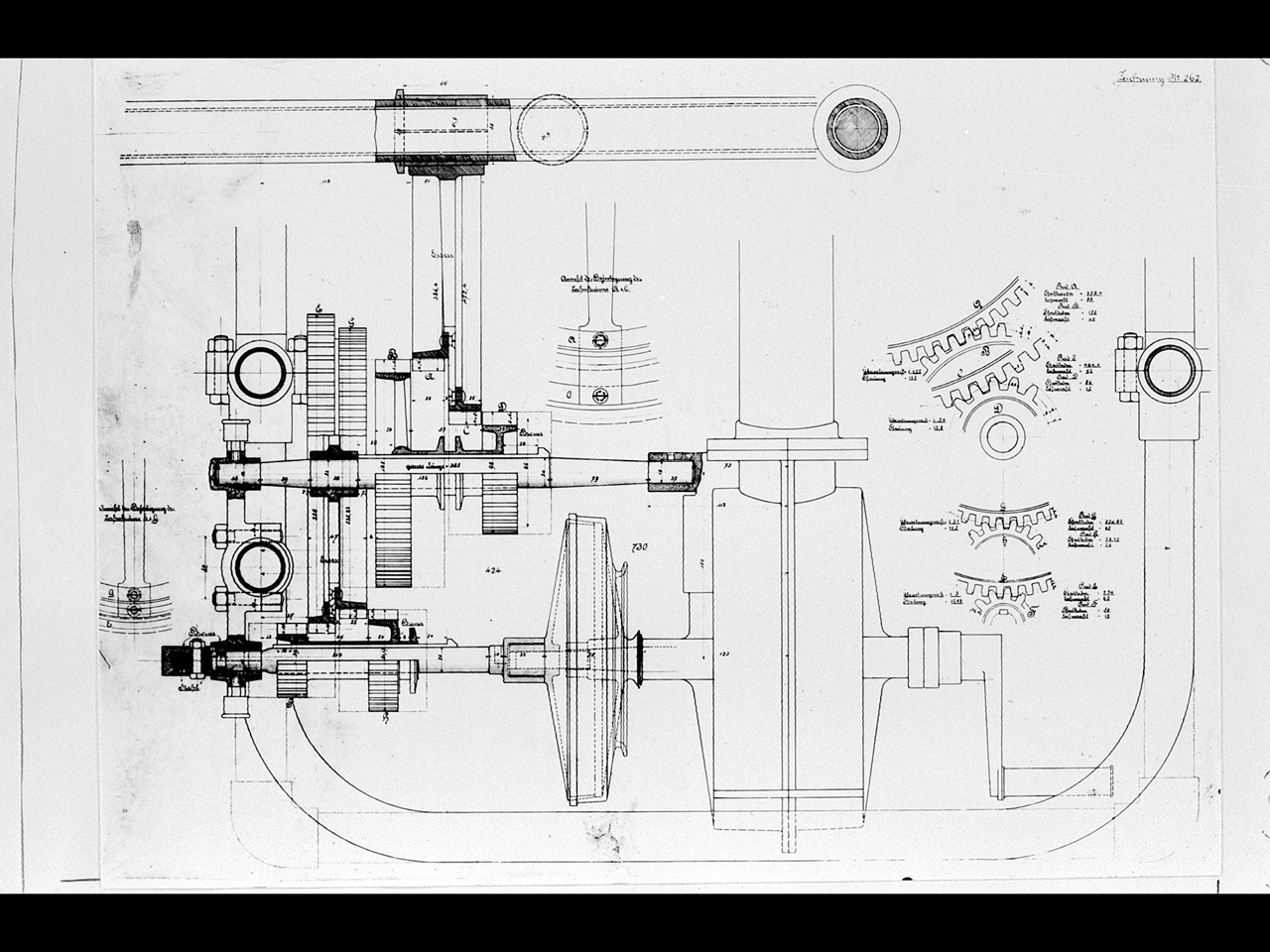

Four-speed geared manual transmission

The wire-wheel car gave Maybach the opportunity to try out his design for a geared manual transmission with four speeds. This consisted of various gear pairings with straight-cut teeth, of which one pair was in service at any given moment. First gear enabled the vehicle to travel at up to 5 km/h, fourth gave a top speed of 16 km/h. During an extended test drive in Paris the transmission was impressive enough to convince an engineer from Renault, the carmaker that had been founded only the previous year. It was so perfect that it became the model for all subsequent gear transmissions for motor cars. The only downside was that technology of the day did not permit optimum hardening of the gear wheels, which meant that service life left something to be desired.

In spite of all the innovations, the wire-wheel car for which Daimler and Maybach had harboured the highest hopes, met with little interest among the visitors to the World Exposition in Paris. Nevertheless, the World Exposition was to be the scene of another event of enormous significance – Gottlieb Daimler cemented a business partnership with Louise Sarazin, the widow of his long-standing French business colleague, Edouard Sarazin. She acquired the licensing rights to Daimler engines on condition that the engines bore the name “Daimler”. This was to prove a catalyst for the French automotive industry, as well as for the widespread growth in general of the automobile – since France would be at the centre of this growth. Before long, there were more cars equipped with “moteurs système Daimler” than in its country of birth, Germany, where distribution was moving ahead at a comparatively slow pace. In addition, French licensees also found profitable business with motor boats, trams, trolley cars, power generators and fire hoses.

In 1890 Louise Sarazin married Emile Levassor. Her husband’s company Panhard & Levassor also supplied engines to other companies. Their biggest customer was the family-run Peugeot company, which bought the wire-wheel car at the end of the World Exposition. Using this as a model, the company began building its own automobiles, supplied exclusively until 1906 with Panhard & Levassor engines produced under the Daimler licence. By the turn of the century Peugeot had become France’s leading car manufacturer.

The wire-wheel car was an important milestone in automotive history. As was the V-engine, of course, which went on to become the drive system for all kinds of vehicles.