1907 Daimler Dernburg Wagen

|

Price |

34,750 Marks |

Production |

-- | ||

|

Engine |

6.8 liter inline-4 |

Weight |

-- | ||

|

Aspiration |

natural |

Torque |

-- | ||

|

HP |

35 hp |

HP/Weight |

-- | ||

|

HP/Liter |

5.1 hp per liter |

1/4 mile |

-- | ||

|

0-62 mph |

-- |

Top Speed |

25 mph |

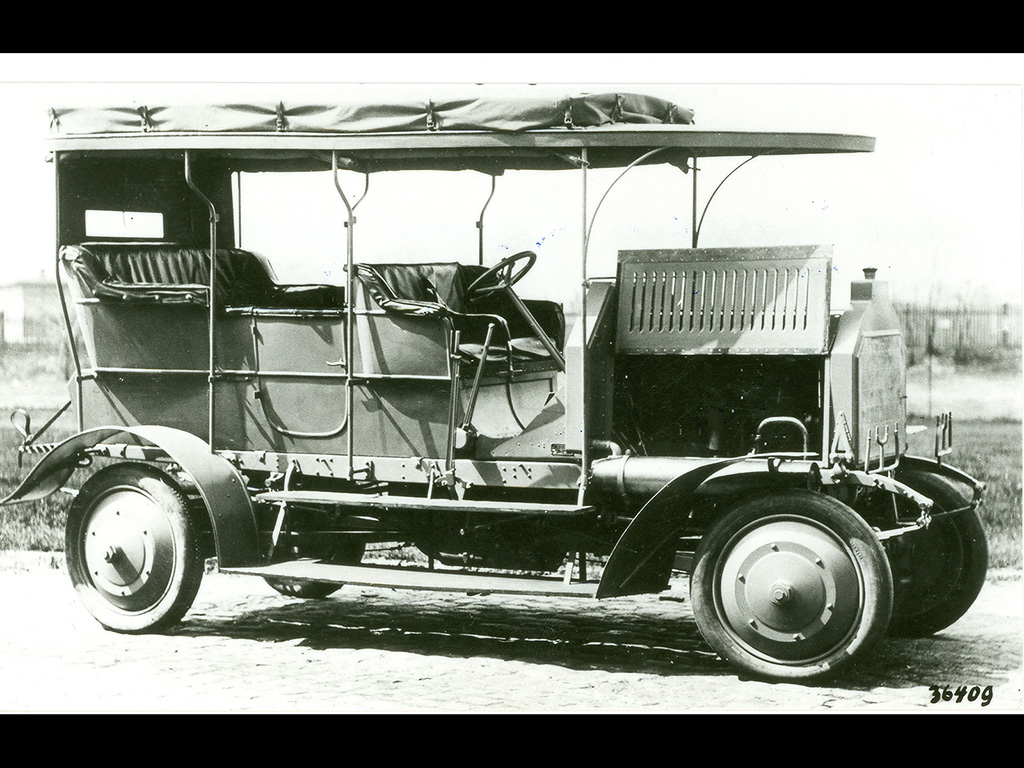

(from DaimlerChrysler Press Release) The world’s first all-wheel-drive passenger car comes from Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft in 1907

* 100 years ago: The “Dernburg-Wagen” features all-wheel-drive and

even all-wheel steering

* Highly sophisticated design by Paul Daimler

* Everyday use in the colony of German South-West Africa, today’s

Namibia

The first all-wheel-drive car for everyday use was built by

Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG) in 1907. The "Dernburg-Wagen", as

it was known, even featured all-wheel steering. It is called after

the then Secretary of State of the Colonial Office Bernhard Dernburg

who drove many a kilometer in it in Africa the following year.

In fact the all-wheel-drive history of the company began slightly

earlier, in 1903, when Paul Daimler laid the foundations for this

technology with a first design draft. The first all-wheel-drive

vehicle appeared in 1904, and was quickly followed by others. Since

then, the watchword has been that all-wheel drive is the best

technology when it comes to better traction and safe, assured

progress. Over the decades it has been successfully used in all

kinds of Mercedes-Benz vehicles, both passenger cars and commercial

vehicles, and from vans to heavy-duty trucks. Some of these models,

for example the G-Class or the Unimog, have gained a legendary

worldwide reputation, and are to be found virtually everywhere on

earth. All-wheel drive also scores heavily in day-to-day driving on

normal roads, however, as the Mercedes-Benz saloons with 4MATIC

demonstrate.

The Dernburg vehicle of 1907

When placing its production order at the beginning of the last

century, the German Colonial Office knew precisely what to expect

from Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft (DMG): a reliable vehicle which

would withstand long journeys on unmade roads without complaint,

while offering the flexibility that the motor vehicle had already

amply demonstrated by the beginning of the last century. The

engineer Paul Daimler, son of the company’s founder, was chiefly

responsible for the design of the new vehicle which was finally

built as a one-off at the factory in Berlin-Marienfelde in 1907.

This all-wheel-drive vehicle was based on a DMG commercial vehicle

chassis, and had a wheelbase of four meters with a track width of

1.42 meters. The ground clearance of 32 centimeters was not

unusually large for the time, as almost all vehicles were often used

on heavily rutted unmetalled roads. In 1908 "Allgemeine

Automobil-Zeitung" (AAZ) wrote this about Daimler’s design: "All

higher road obstacles are overcome by the robust front and rear

axles, and the particularly vulnerable lower section of the gearbox

housing is enclosed by a strong steel guard between the pressed

frame cross-members, which is resistant enough to allow the entire

frame to bottom."

The vehicle came on the market for a price of 34,750 Marks. It was

fitted with a touring car body having two seats on the chauffeur’s

bench and four seats in the rear. Only the rear passengers had

doors, and large steps were provided to overcome the entry height of

around one meter. Extending almost to the front end and mounted on

eight poles, a sunshade prevented the driver from being dazzled even

when the sun was low. A luggage rack was mounted on the back for

cases or spare tires, with a further, large luggage rack on the roof

protected by a tarpaulin. Awnings were affixed below the roof on

both sides; these could be lowered to enclose the body and protect

the occupants from wind, weather and sand. "To be sure, this

Mercedes is not noticeable for its light and elegant construction;

it has unmistakable external signs of power and endurance," wrote

AAZ, however: "The overall impression of the vehicle has not

suffered as a result of the special requirements."

Matched to operating conditions with numerous special features

With a length of around 4.90 meters and a height of a good 2.70

meters including the roof structure, the majestic vehicle weighed

around 3.6 tonnes when fully laden with all the special items

specified by the Colonial Office, such as a particularly heavy-duty

clutch and petrol and coolant reserves for tropical conditions,

replacement parts and tools.

Despite this the four-cylinder engine performed manfully, delivering

a very respectable output of 35 hp (26 kW) from a displacement of

about 6.8 litres at 800 rpm – allowing a maximum speed of around 40

km/h on level tarmac. In view of the intended operating conditions,

the climbing ability made possible by the all-wheel drive was

however more important: it was an outstanding 25 percent. The

vehicle featured permanent all-wheel drive, the engine delivering

its power to the four wheels via a sophisticated mechanical system.

A shaft connected it to the centrally installed gearbox, which had

four forward gears and one reverse gear. From there prop shafts

transferred the torque to the front and rear axle differentials,

which in turn used bevel gears to split and transfer it to the

wheels.

Mechanical components protected against airborne sand

The designer Paul Daimler took special precautions to keep airborne

sand out of the drive components. Many of the joints were packed

with lubricating grease to keep sand at bay and prevent rapid wear,

but the front axle proved to be a real challenge at first: owing to

the expected heavy impacts and fine airborne sand, it was not

possible to use the usual protection for the bevel gears on the

wheels, a telescopic system which followed the steering movements.

Daimler shrouded the vulnerable components with a robust,

cylindrical sleeve, but because this solution limited the maximum

steering angle to just 23 degrees, the vehicle was also equipped

with steered wheels at the rear to achieve a reasonable turning

circle. The rear wheels were also encapsulated as a protection

against airborne sand. One positive side-effect was that the front

and rear axle components, including the differentials, wheels and

brakes, were of identical construction, which considerably

simplified the provision of replacement parts.

The solid steel wheels also served to protect the mechanical

components and drum brakes against soiling; wheels with wooden (and

more rarely steel) spokes were usual at the time, however these

would have let sand into the drive components. Moreover, spoked

wheels would have made it practically impossible for the vehicle to

free itself after sinking into the sand. The steel wheels were shod

with size 930 x 125 pneumatic tires, another unusual feature as

solid rubber tires were still in widespread use at that time.

Presumably Paul Daimler made this choice to assist the robust leaf

springs in their work in view of the vehicle’s high weight. Not

unusually for the time, only the rear tires carried a tread while

the front tires had a smooth surface. The tire valve was located on

the inside of the wheel so that it was not so exposed to damage.

The cooling system was specifically configured for the tropical

climate, with a larger cooling surface, a larger cooling mantle

around the cylinders and more coolant – the circuit contained 140

litres in total. In addition to the radiator at the front end, a

second radiator was mounted on the front bulkhead, enclosing it in

horseshoe fashion and extending its honeycomb structure into the

slipstream. Both radiators were connected via two side-mounted water

reservoirs, and the heated water had to pass through all the lines

and tanks before flowing around the cylinders again. "Even in deep

sand at only 8 km/h, the cooling system performed admirably during a

one-hour endurance test," AAZ reported.

Extensive testing under realistic conditions

At the end of March/beginning of April 1908, the colonial vehicle

was subjected to a thorough, 1677-kilometer trial in Germany. The

route ran from Berlin-Marienfelde to Stuttgart-Untertürkheim and

back. Untertürkheim was reached during the morning of the fourth

day, and four days later, the car was back in Marienfelde. The route

included off-road sections, too, so as to test the all-wheel drive.

“A turn in a deeply ploughed field with a gradient of five to ten

percent was negotiated impeccably,” a Colonial Office report stated.

“Near Wittenberg the vehicles was driven into a sandpit, in which it

sank well up to its axles in the sand, but from which it managed to

free itself with ease despite gradients of 20 and 21 percent.” In

the Thuringian Forest, “a hill approximately 150 meters high was

climbed on stony, twisting, narrow roads with gradients of up to 20

percent without difficulty. Even the steering, which was inherently

cumbersome as a result of the four-wheel drive, proved itself.” The

Colonial Office’s test report was positive.

In May 1908 the vehicle was shipped to Swakopmund in Africa on board

the “Kedive”. The Secretary of State at the German Colonial Office,

Bernhard Dernburg (1865 -1937) received it for his personal disposal

in German South-West Africa one month later. His task was to

coordinate and improve relations between the colonies and the

motherland. As a result of his travels the all-wheel-drive vehicle

was nick-named the "Dernburg-Wagen" many years later. At the same

time, these trips served as a general test of the motor vehicle as a

means of transport in the colony, and to this purpose the

all-wheel-drive “Dernburg” was accompanied at least some of the time

by other, rear-wheel-drive, vehicles from Benz and Daimler, namely a

seven-seater, extensively armoured car from Benz and three trucks

from Daimler.

The author of a travel report from that time described a journey

with the Dernburg as follows: “The 600-kilometer trip from

Keetmanshoop via Berseba to Gibeon and then from Maltahöhe, Rehoboth

to Windhoek was made in a journey time of four days without

accident. That is an enormous time-saving, since for the same

journey an accomplished rider takes twelve days on horseback […].”

And the official was even able to use a mobile communication aid,

too: “When [the vehicle] was carrying Secretary of State Dernburg,

it also took a field telephone which was able to be tapped into the

telegraph wires anywhere along the way.”

In permanent service by the police

Following this trip, the car was made available to the police in

German South-West Africa as a means of transport on a permanent

basis. A precise log was also kept, showing for instance that the

vehicle had covered around 10,000 kilometers by the beginning of

1910.

The car’s driver, who also doubled as its mechanic, was sent by

Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft along with the vehicle – common

practice at the time. And since it belonged to the police, without

further ado driver Paul Ritter was made a policeman. Following

Dernburg's departure, Ritter remained in the country to look after

the car, repeatedly returning to Marienfelde so as to acquire the

required spare parts, as well as the repair and maintenance skills

to go with them.

The details known about the “Dernburg” all point to the engineering

ability of Paul Daimler, who tailored the car’s design precisely to

its intended application. Every single feature was thought through

so that the vehicle made no compromises with regard to its chief

purpose – driving in trackless terrain.

Despite this, the journeys undertaken with the car did not go as

smoothly as those involved would have liked. This was because its

high weight, due in large measure to the Colonial Office’s special

requirements, meant that the pneumatic tires were subjected to a lot

of punishment. This meant that, particularly with the amount of

off-road driving that had to be done, they only lasted a

comparatively short time – 36 tires and 27 inner tubes were used up

in the above-mentioned 10,000 kilometers covered by early 1910.

Experiments with solid rubber tires proved unsuccessful, since the

forces acting on the wheels were then too much, and destroyed them.

The all-wheel drive, by contrast, proved its worth particularly on

sandy surfaces, on which the car made better progress than the

accompanying rear-wheel-drive trucks. Despite this, after a detailed

inspection a police colonel submitted a recommendation to convert

the car to pure rear-wheel drive: the numerous components of the

all-wheel-drive system made it complicated and time-consuming to

maintain and repair. This conversion then apparently did actually

take place, but the precise details have not been handed down. There

are no records on how the car was used during the First World War.

After it, and after the end of German colonialism, all trace of the

“Dernburg” was lost – its fate is unknown. Paul Ritter, its driver

and mechanic, returned to Marienfelde in 1919 where he once more

found employment with Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft.