1940 BMW 328 at Mille Miglia

|

Price |

-- |

Production |

-- | ||

|

Engine |

-- |

Weight |

-- | ||

|

Aspiration |

-- |

Torque |

-- | ||

|

HP |

-- |

HP/Weight |

-- | ||

|

HP/Liter |

-- |

1/4 mile |

-- | ||

|

0-62 mph |

-- |

Top Speed |

-- |

(from BMW Press Release) A victory of passion and precision.70 years ago BMW won the Mille Miglia.

1.1. An enduring milestone

Munich. 70 years ago the

racing department at BMW had only one thing on its mind: the 1st

Gran Premio Brescia delle Mille Miglia. Five cars from Munich were

registered for the big race, but preparations were not exactly

worry-free. Indeed, the team ultimately faced a battle to get the

cars ready in time. However, as the BMWs crossed the finish line one

by one in Brescia on 28 April, they had achieved what few had dared

to expect: overall victory, team victory, and third, fifth and sixth

place in the rankings. That April day witnessed BMW’s greatest

racing success so far on four wheels – and one which continues to

define the character of the brand today. “The victory in the 1940

Mille Miglia remains a milestone in the history of the BMW brand,”

says Dr Klaus Draeger, member of the BMW Group Board of Management

responsible for development. “It is evidence not only of

extraordinary technical expertise but also of the passion shared by

all those involved at BMW.”

The 1940 Mille Miglia was the climax of a journey that had begun

with the design and presentation of the BMW 328. The BMW 328 was not

only one of the most beautiful sports cars of the prewar era, it was

also the most successful sports car on the race tracks of Europe in

the 1930s. A combination of outstanding roadholding and impressive

engine power made it an object of desire for many racing drivers and

offered private customers a taste of what undiluted roadster driving

was all about.

A car for the friends of the company

A small brochure

circulated among a select group of people in late 1935 revealed the

existence of a new 2-litre sports car to be known as the “Typ 328”.

The description of the car was deliberately low-key and avoided

giving any performance or speed figures. The brochure was intended

purely as an appetiser for “friends of the company”; there was no

announcement in the press.

Journalists were left open-mouthed when they set eyes on the car for

the first time in the Nürburgring paddock on 13 June 1936. There,

Ernst Henne was preparing to race the 328 in the International Eifel

Race the following day. The motorcycle world record holder roared

away from his rivals off the start line and soon left the rest of

the field trailing in his wake with a phenomenal average speed of

101.5 km/h. This show of strength from the 328 had commentators

purring about the future of the German sports car. However, few

could have guessed that they were witnessing the dawn of a new era.

Few observers are likely to have fully grasped what was unfolding in

front of them that day. In an earlier press release BMW had itself

downplayed the new model as a “2-litre sports car with a slightly

more streamlined body”, lulling some journalists – who referred only

to its “2-litre V engine with twin camshafts” – into a misplaced

sense of the ordinary. The understated approach might well have been

a tactic on BMW’s part to avoid raising hopes too high, too quickly;

after all, by that point only three prototypes had been built.

The wins keep coming

The second victory for

the 328 arrived in August, with British BMW importer H.J. Aldington

sweeping all before him in the Schleissheimer Dreiecksrennen race.

Aldington then persuaded the powers-that-be at BMW to give the car

another run outside Germany. The three prototypes duly made their

way to Ireland for the Tourist Trophy sporting green Frazer-Nash-BMW

livery – and cantered to a 1-2-3. The 328 had got the ball rolling

and several more victories followed over the ensuing months.

However, it was still the three pre-production cars taking it in

turns to rack up the wins, with various drivers at the wheel.

Private customers were forced to play the waiting game, as

production was slow to get off the ground; the first cars were not

delivered to customers until late April 1937. And so it was exactly

a year since Henne’s debut outing before the first private owner of

a BMW 328 had the chance to test his new purchase in race action.

At the 1937 Eifel Race it was left to the nine BMW 328 racers on the

grid to fight it out for victory. Over the years that followed only

a handful of cowed attempts were made by other cars to take on the

hot-heeled BMWs. These intrepid lone rangers were doomed to failure

as the BMW 328 quickly took Germany’s race tracks by storm.

Reports of victories continued to rain into Munich from every corner

of Europe. And it wasn’t only class wins that the car was amassing

so effortlessly, as much more powerfully-engined cars also succumbed

to its irresistible will. The small 2-litre sports car was building

a handsome collection of overall victories over once superior

rivals.

1.2. Dress rehearsal – the 1938 Mille Miglia

1937 had been a hugely

successful year for BMW and its new sports car. The BMW 328 had run

out of rivals in the 2-litre class in Germany, and it had also put

itself on the radar of sports car drivers in other countries with a

string of successes abroad, mostly with Ernst Henne at the wheel.

Now BMW needed the big international breakthrough, a triumph on

foreign soil that would make headlines far and wide.

While central Europe remained firmly in winter’s grip, south of the

Alps the motor sports community was priming itself for a race which

had, over many years, become one of the most famous on the calendar:

the Mille Miglia. On 3 April 1938 this legendary road race, starting

for the 12th time from Brescia and leading through half of Italy,

would send a whole nation into an unimaginable frenzy of enthusiasm.

Preparations had been under way for months already, garages humming

to the sound of racing cars flexing their muscles. At the Munich

racing department, too, the engineers were hard at work, readying a

brace of works cars for action.

The race organisers had revised the class boundaries for the 1938

event. The national sports car class was joined by categories for

international sports cars with and without a supercharger. Of the

155 drivers entered for the race, 119 lined up in the national

class, highlighting the Mille Miglia’s status as first and foremost

an Italian national event. The smallest class in which international

drivers could compete was therefore the 2-litre sports car class.

In 1938 the organisers set out to encourage more foreign, i.e.

German, drivers to take part. However, only four drivers responded

to the appeal, all entering BMW 328 racers. The NSKK (National

Socialist Motoring Corps) registered Prince Max zu Schaumburg-Lippe

as its driver and – as a manifestation of the German-Italian

friendship – the experienced Mille Miglia campaigner Count Giovanni

Lurani as co-driver. BMW sent two works cars to the race, one manned

by privateer drivers Uli Richter and Dr Fritz Werneck, the other

piloted by Britain’s A.F.P. Fane with William James alongside as his

mechanic and navigator.

These three cars made up a team managed by Ernst Loof, head of the

BMW racing department, and they were joined by the privately-entered

driver/mechanic pairing of Heinrich Graf von der Mühle-Eckart and

Theodor Holzschuh, an employee at the BMW sports car repairs

department. Also on the start list were a Fiat, a Riley and an Aston

Martin.

Top of the class

The weather for the race

could hardly have been more perfect. Brescia had been basking in

spring warmth for several days already, and only at the start of the

race was there a slight chill in the air.

The centre of Brescia was alive with anticipation over the night

from 2–3 April. Thousands of excited onlookers had gathered at the

start and lined the roads leading into the city to witness the

unfolding of this extraordinary event. At 2.00 a.m. the first cars

in the smallest-capacity section of the national class were waved on

their way. The cars started at 30-second or one-minute intervals,

according to the class. The long list of entrants meant that the

first test for the drivers of the larger cars was one of patience.

At least they could relax in the knowledge that they would be

driving in daylight, although that also meant they would have a lot

of overtaking to do.

By contrast, darkness had yet to yield when the cars in the 2-litre

class were called to the starting line. Prince Schaumburg was the

first to set off into the Italian night, on the stroke of 4.30 a.m.,

followed by Uli Richter, the three non-BMW cars, Fane and von der

Mühle-Eckart. The BMW racers wasted no time in setting a withering

pace, showing enviable confidence in the durability of their

beautifully prepared race engines. By the time they reached Rome

they had already seen off the challenge of two of the other

manufacturers in their category, and the third was forced to retire

shortly afterwards. But the BMWs were not about to slow down to

celebrate. Quite the opposite, in fact. With their class rivals out

of the picture, they were free to launch an attack on the more

powerful cars. The Germans were driving with clockwork precision,

and only a few minutes separated them at any one time.

The fastest drivers arrived back in Brescia in the late afternoon.

Less than 12 hours after crossing the start line, the powerful

supercharged Alfa Romeos, the Delahayes and the Talbots were back at

base, as expected. The big surprise, though, was still to come; Fane

steered his BMW 328 to eighth place in the overall classification,

winning the 2-litre class and leaving a considerable number of

supercharged cars in his wake in the process. Fane’s fellow-BMW 328s

followed him home in 10th, 11th and 12th overall, securing 2nd, 3rd

and 4th places in their class and rounding off a spectacular race

for BMW. Added to which, they also won the team prize for

consistency and the award for the best foreign entrant.

BMW’s pride in claiming the biggest win in the company’s history was

obvious. The 328 had proved that it was capable of sustaining

incredibly high speeds over long distances without complaint. The

car’s combination of impressive output and flawless roadholding had

shown that it was possible to defeat the challenge of far more

powerful rivals. For BMW this success represented the international

breakthrough in European motor sport.

1.3. Streamlined design to boost efficiency – the BMW racing saloons

In the 1930s the

regulations governing motor sport in Germany decreed that a racing

sports car had to be open-topped. The BMW 328 was a roadster in the

classical mould, but there were also a few hard-top examples of the

328 in circulation, and for a short while two of these found

themselves very much in the public glare.

Since its maiden outing in the 1936 Eifel Race, the BMW 328 had

quickly established an iron grip over Europe’s race tracks. For the

engineers in Munich, however, this was no reason to rest on their

laurels. Instead, they were working flat out on increasing the car’s

original output of 80 hp. Rival manufacturers had already boosted

their engines to something close to 110 hp, but a significant rise

from that level was not expected. There was certainly little scope

to further reduce the weight of what was hardly a heavy car in

standard production form. The only way to increase its speed was to

reduce drag. The curvaceous form of the 328, with its prominent

front wings, may have been a masterstroke of engineering and design,

but it was less than ideal aerodynamically. The BMW engineers were

therefore charged with designing a totally new body based on the

latest knowledge from aerodynamics research.

Closed beats open

Tests had shown that an

enclosed saloon, despite its larger cross-sectional area, could

outperform an open sports car using airflow optimisation measures.

Convincing performances in the Le Mans 24-hour race in 1937 and 1938

allowed the Frankfurt-based firm Adler, who introduced the first

“racing saloons” to competitive action, to demonstrate clearly how

streamlined bodies could balance out a deficit in engine power.

BMW had been investigating this area of car development at the same

time, but it was Professor Wunibald Kamm, head of the Research

Institute of Automotive Engineering and Vehicle Engines at the

Technische Hochschule Stuttgart (FKFS), who conducted the first wind

tunnel tests with BMW models.

The BMW engineers were now working under considerable pressure. As a

celebration of the Berlin-Rome Axis, the German and Italian racing

authorities had decided to organise a high-speed race in October

1938 on the newly built motorways between the two capitals of

fascism. For BMW and the other manufacturers involved, this meant

developing a high-performance sports car in double-quick time, one

which could not only hold its own in race competition, but also had

a realistic chance of overall victory.

High speed, low stability

Rudolf Flemming, who had

played a major role in the design of the 328, was instructed to make

the car with a closed roof in order to use all the benefits of

streamlined design. However, this ruled it out of sports car races

in Germany as closed cars were not permitted. Guided squarely by the

principles of lightweight design, Flemming designed an intricate

space frame for the 328 chassis and covered it in a thin aluminium

skin.

However, the car known internally as Project AM 1007 was far from

convincing. The Eisenach-built body fell short of the mark in terms

of workmanship, and the car’s handling left a great deal to be

desired. While the car achieved previously undreamt-of speeds on

test runs, it was so unstable that it needed the full width of the

motorway to do so. A huge amount of development work was still

required to turn this into a racing car worthy of the name.

The efforts of BMW to get a fast car up and running had not gone

unnoticed outside the company. Back in the spring of 1938 the NSKK

had founded its own racing operation, a self-styled German national

team for sports car racing. Its aim was to fly the German flag at

events abroad with its own trio of BMW 328 racing cars. The BMW

factory had a contractual obligation to keep the NSKK cars up to the

latest stage of development, but its new racing saloon represented a

potential rival to the NSKK team – one that had to be taken

seriously. Under no circumstances could a works driver be allowed to

jeopardise the victory the NSKK team had set its sights on. However,

when Prince Max zu Schaumburg-Lippe, the team’s leading driver,

demanded he also be given a racing saloon, BMW responded that they

had no spare capacity to built one.

The Touring Coupé

Schaumburg-Lippe was

therefore left with no other option than to shop around among his

allies. The Mille Miglia had offered clear evidence that smaller-engined

cars could achieve extremely high speeds through the use of

lightweight, streamlined bodies. Now, a year later, Germany’s good

relations with Italy helped to prompt an offer from Carrozzeria

Touring to produce a streamlined body. The Milan-based coachbuilder

was already working on a similar project for Alfa Romeo and could

call on previous experience for the job, having built a body of the

same type a year previously. This streamlined construction in

patented superleggera form could be adapted to the standard 328

chassis with no great trouble, and the Italian craftsmen came up

with the finished article in just four weeks.

With no wind tunnel testing available at Touring, the engineers

successfully relied on instincts and empirical methods to give the

car the right form. The Coupé weighed in at just 780 kg and looked

resplendent in German racing white, but it was far more than just a

pretty face. Test runs had shown that it was capable of exceeding

the 200 km/h mark – and holding a relatively straight line in the

process. The Touring Coupé lined up for its debut race at Le Mans on

17 June 1939 with Prince Schaumburg and BMW engineer Hans Wencher

entrusted with the driving duties. After 24 hours and 3,188

kilometres, the pairing emerged triumphant in the 2-litre class with

a sensational average speed of 132.8 km/h. They even managed an

outstanding fifth position in the overall classification, getting

the better of much larger-engined cars along the way.

The Kamm Coupé

The success of the

“Cinderella” Touring Coupé was greeted with mixed feelings at BMW.

However, the engineers at the development department had not been

idle themselves. Extensive wind tunnel testing had revealed that the

Project AM 1007 streamlined body did not fit the chassis. The newly

formed “Künstlerische Gestaltung” design department headed by

Wilhelm Meyerhuber was therefore asked to draw up a new streamlined

body under project number AM 1008.

In order to improve the car’s straightline stability, the chassis

was extended by 20 centimetres. The newly developed space frame,

made from Elektron, weighed just 30 kilograms. Taken as a whole with

the aluminium outer skin, this meant BMW now also had a “superlight”

body in its arsenal.

The Kamm Coupé was significantly larger than the comparable Touring

variant, but a rigorous adherence to lightweight design principles

meant it was also 20 kilos lighter. It took several months to put

the car together due to restricted capacity in the prototype

construction department. But, in contrast to their Italian

counterparts, BMW engineers were able to put their works racing

saloon through extensive testing. In late summer 1939 the car was

given a thorough examination on the Munich to Salzburg autobahn and

further improvements were made to a host of details.

The investment of time and effort was to pay dividends. The Kamm

Coupé had much better directional stability and proved to be far

less sensitive to side winds. A Cd of approximately 0.25 (measured

using a model) was well below the Touring Coupé’s figure of approx.

0.35. The works car also set a new benchmark in terms of speed,

hitting a maximum 230 km/h. However, with the outbreak of war nobody

knew whether it would ever get the chance to show off its talents.

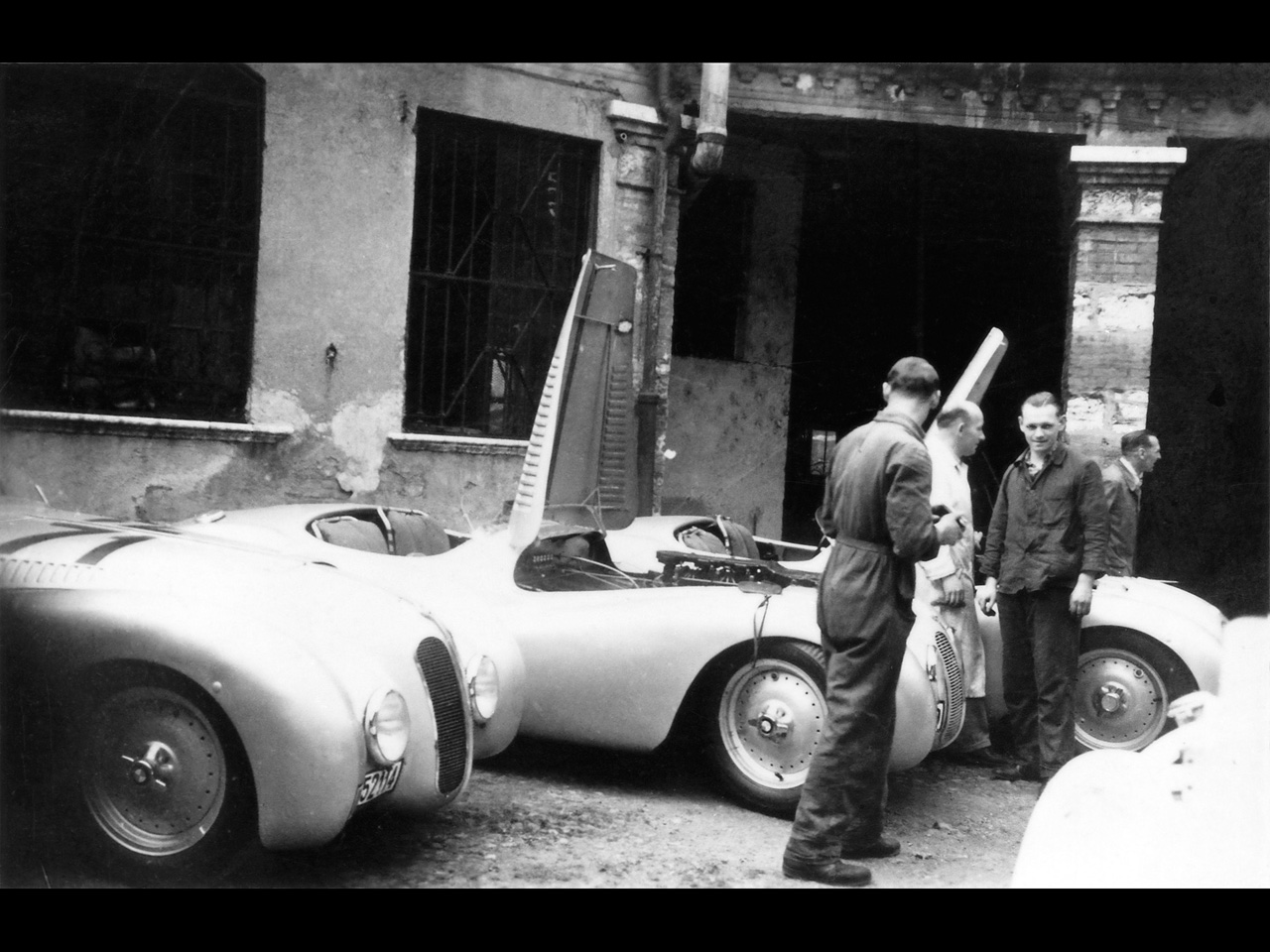

The Roadster

There were also advances

in streamlined design to report in open car construction. The design

team headed by Wilhelm Meyerhuber tabled designs for a streamlined

Roadster whose sweeping body created the impression of dynamic

performance and speed even before a wheel was turned. Models were

also made of the Roadster and subjected to intensive testing in the

Stuttgart wind tunnel. Then, in autumn 1939, a space frame was fixed

to the standard chassis of the previous year’s Mille Miglia class

winner and covered with a thin aluminium skin. The prominent edging

of its front wings soon earned the car its nickname: the “Trouser

Crease” Roadster.

The next step was to optimise the car’s chassis tuning. To this end,

Munich-based racing driver Uli Richter was handed the task of taking

the finished car out in the icy cold for a series of high-speed runs

along the autobahns outside Munich. However, the streamlined

roadster required only minimal improvements. Another two space

frames had already been mounted to the requisite chassis, but the

clock was starting to tick. The body department in Munich was

understaffed for the job in hand, as BMW only built cars in Eisenach

at the time, and there were fears that the two racers would not be

ready to meet the spring deadline. If ever there was a time to tap

into those good relations with Milan again, this was it. The two

half-finished racing cars were duly transported over to Touring, and

the experienced Italian coachbuilder had no problem in finishing off

the cars in a short space of time. Willy Huber, the racing

department’s very own master of all trades and a gifted metalworker,

travelled with the cars to Milan and was on hand to advise his

Italian colleagues when it came to working with the aluminium

sheeting.

1.4. BMW reaches its zenith – the 1940 Mille Miglia

Spring 1940. In Italy

all attentions are focused on bringing the Mille Miglia back to

life. The legendary race had last been run over the historic course

in 1938. However, after a rash of accidents it had been temporarily

suspended. Now, two years later, the Mille Miglia was back in

business, but the original route had been dropped in favour of a 167

km triangular course between Brescia, Cremona and Mantua. The

drivers would complete nine laps of the new circuit, a move warmly

welcomed by the watching pubic, who only saw the cars fly by once

when the race followed its original route.

The new route was not as spectacular, though. It followed

well-surfaced roads through flat countryside and included a lot of

long straight sections which were expected to lead to high average

speeds. In a nod to tradition, the race was once again billed the

1st Gran Premio Brescia delle Mille Miglia.

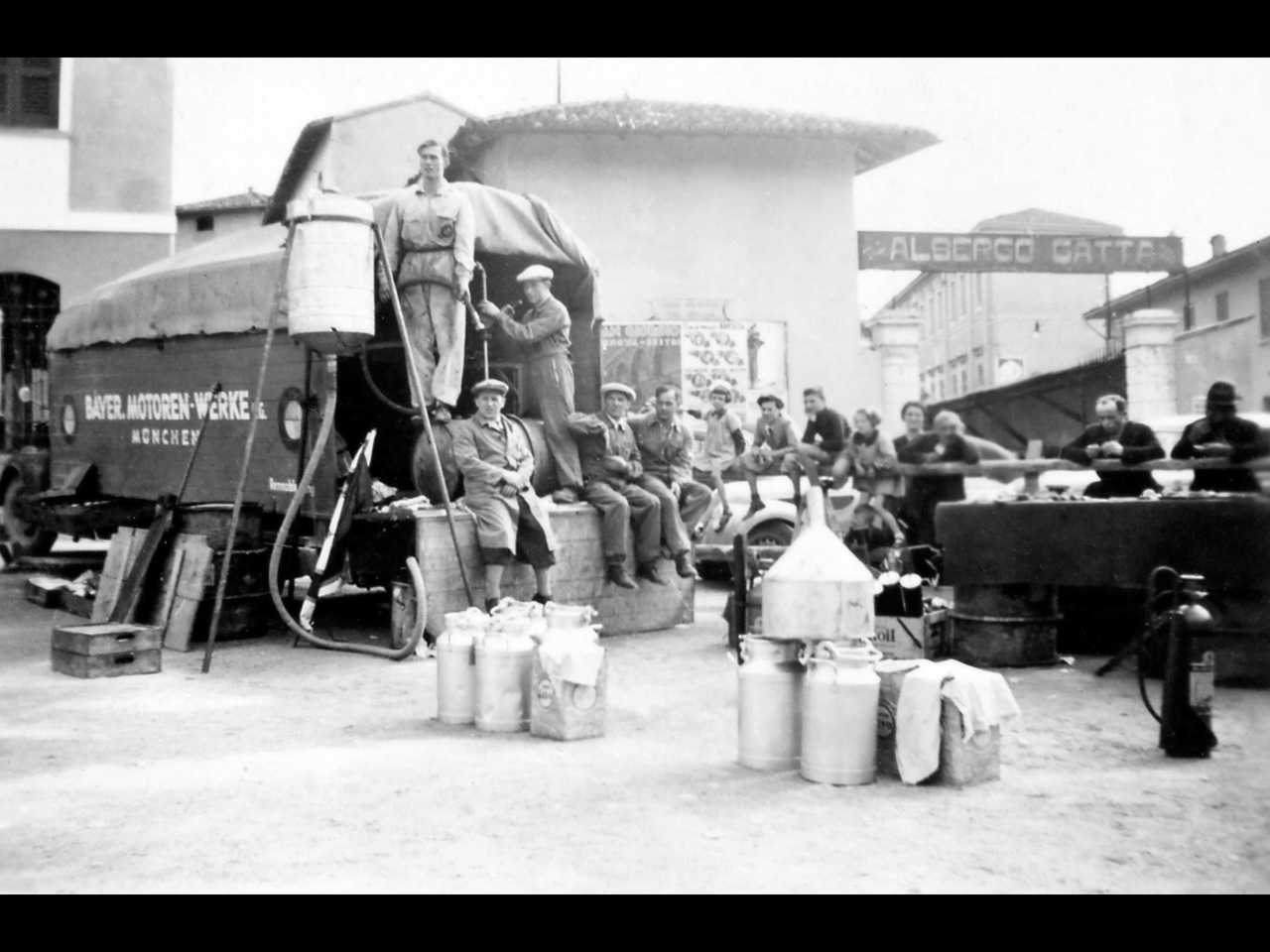

Planning for the German entry got under way with military precision

in March 1940. BMW racing boss Ernst Loof travelled to Italy with a

group of drivers, the two Coupés and a single Roadster to

familiarise themselves with the route, work out a race strategy and

organise the building of their garage. Working according to average

fuel consumption of 20 litres per 100 km, the course was split into

three 500 km sections. On this basis, the ideal location for a

garage turned out to be Castiglione, some 25 km outside Brescia.

This would be the topping-up point for fuel and oil, and Loof could

take the opportunity to pass on any necessary instructions to his

drivers here.

Silver, red and blue

In the final three days

before the race the drivers gathered with their cars for technical

inspection at the Piazza della Vittoria in the centre of Brescia.

Among them were the five German BMWs with their silver paintwork.

The starting field was dominated in traditional fashion by the red

cars of the local contenders. 70 Italian driver teams would line up

for the race in FIATs, Lancias and Alfa Romeos. They would be joined

by two blue cars from French manufacturer Delage, also with Italian

drivers at the wheel.

The members of the NSKK team were entered to drive the three

streamlined Roadsters, having represented Germany with great success

in races abroad over the previous two years. Car number 71, the

first streamlined Roadster, was piloted by Hans Wencher and Rudolf

Scholz, the two other Roadsters – car numbers 72 and 74 – were

crewed by Willi Briem/Uli Richter and Adolph Brudes/Ralph Roese

respectively. The three teams were under instructions not to push

too hard, but to maintain a good speed and look after their

machinery. Although the aim was to finish as high up the standings

as possible, the main priority was to complete the race and win the

team prize.

The two Coupés, meanwhile, were entered by the ONS (the

highest-ranking national sports authority in Germany at the time).

Fritz Huschke von Hanstein and Walter Bäumer would drive the Touring

Coupé, while two outstanding Italian drivers – Count Giovanni Lurani

Cernuschi and Franco Cortese – had been recruited to pilot the works

Kamm Coupé. While the target for these two Coupés was overall

victory, tradition suggested that the Alfa Romeo team was a far more

likely winner. BMW’s Italian driver pairing were certainly in with a

chance, though, the Kamm Coupé having displayed superior handling in

testing and reached much higher speeds than the Touring Coupé.

Set out as you mean to go on

28 April, 4.00 a.m. The

cars are sent on their way at one-minute intervals. Von Hanstein/Bäumer

– in the first BMW – entered the fray at 6.40 a.m., followed by

their team-mates and the Italian drivers in the largest-capacity

class. The youngster von Hanstein set out his stall from the off,

covering the first lap at a speed nobody present had thought

possible. Already, the gap between the BMW driver and his closest

pursuer in a Delage was one and a half minutes. Lurani/Cortese,

meanwhile, were lying third in the second BMW Coupé, followed by one

of the highly fancied Alfa Romeos. The three Roadsters were biding

their time in seventh, eighth and ninth positions.

On the second lap the two BMW Coupés led the way, with the Italians

locked in a battle with the charging streamlined Roadsters. However,

the Kamm Coupé could not keep up such a breakneck pace for long. It

was hit by problems first with the carburettor, then with the oil

supply, and on lap 7 the hugely disappointed driver pairing were

forced to retire from the race.

The Touring Coupé, meanwhile, was continuing to reel off the fast

laps undeterred. Indeed, von Hanstein set the fastest time ever

recorded in a sports car race with an average speed of 174 km/h.

However, there was the odd difference of opinion between von

Hanstein and his co-driver Bäumer, as the ambitious baron was

determined to win the race and ignored the pre-arranged driver

changeover. In the end, Bäumer had to be persuaded to settle for the

role of co-driver in order to make sure of the win. The Coupé was

gradually building up an unassailable advantage over the chasing

pack, though, and the two men finally swapped seats a few kilometres

from the finish. In the end, it was Walter Bäumer who had the

privilege of driving the Touring Coupé across the line to claim

overall victory.

Munich celebrates

Unsurprisingly, celebrations were decidedly muted among the Italian crowd. Instead, the packed stands were immersed in a collective sense of bewilderment. What had happened to the red cars? Over 15 minutes passed before the Alfa Romeo of Farina/Mambelli came home in second place, followed by Brudes/Roese in third, Biondetti/Stefani in fourth, Briem/Richter in fifth and Wencher/Scholz in sixth place. BMW had topped both the team and overall standings, and great shows of excitement awaited the crew on their return to Munich. Odeonsplatz and the Residenz (Royal Palace) provided an impressive setting in which to display the winning car to the people of Munich.